At the recent high-profile COP26 UN conference in Glasgow, a number of key agreements were reached to ‘phase down’ coal, end fossil fuel subsidies, stop deforestation by 2030 and cut methane emissions by 30%[1]. However, in the run-up to COP26 and at the summit itself, attention was drawn by figures such as the UK chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance to the role of the individual and behavioural change[2]. Greener behaviour, such as reducing meat consumption and air travel, using public transport and avoiding plastics, is seen by many as vital to the fight against climate change: people’s habit changes are projected to account for 59% of emissions reductions for the period 2020-35[3]. But government attempts to encourage such changes are not without controversy: famously, the anti-government gilets jaunes protests which rocked France in 2018[4].

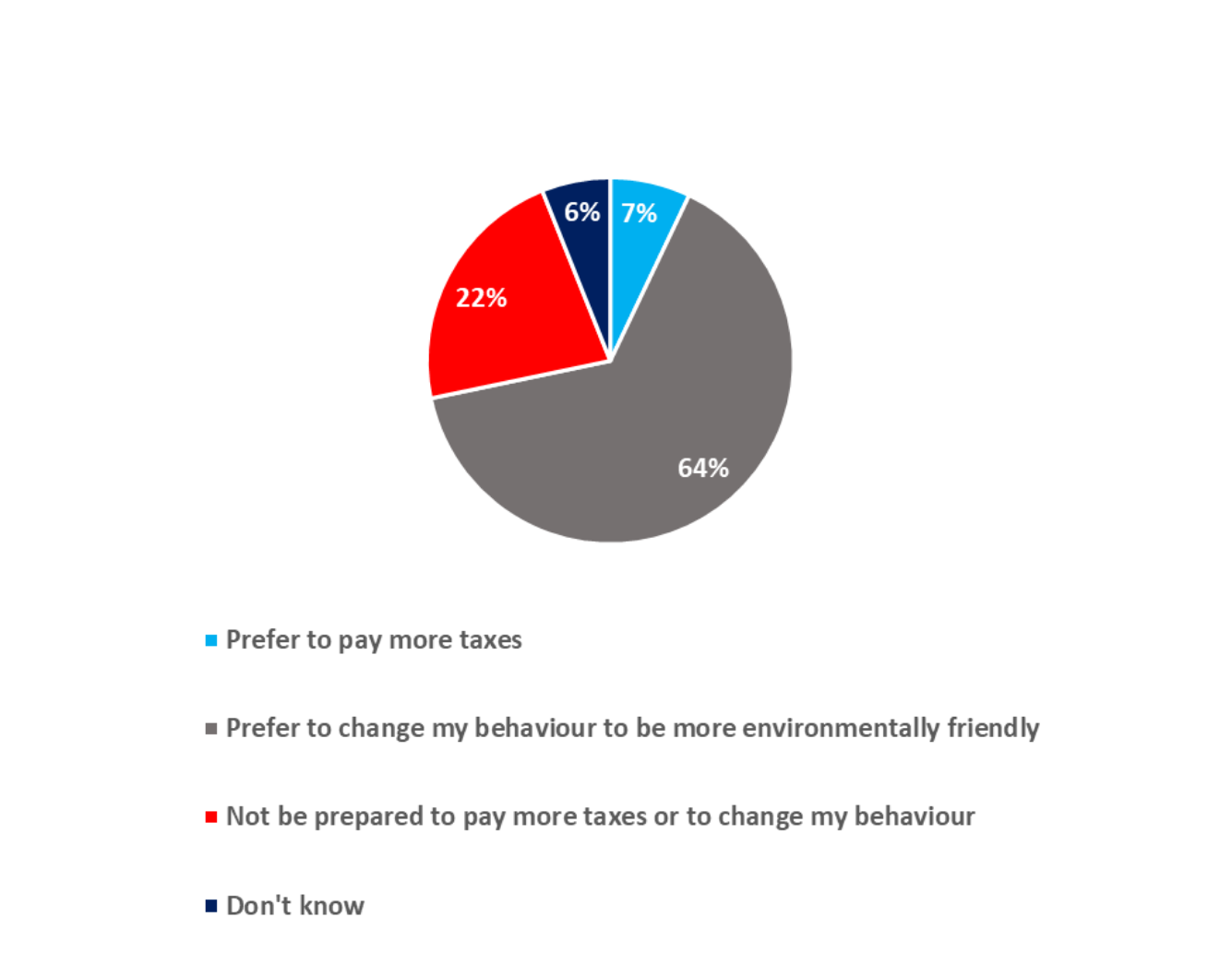

Shortly after COP26’s conclusion, the Serco Institute commissioned independent polling experts at Survation to conduct a single-question survey asking respondents whether they would prefer to pay more in taxes or to change their behaviour, or neither, to reduce carbon emissions. By some margin, the British public indicated that behavioural change was their preferred means of reducing emissions: 64% of respondents supported this option. Perhaps worryingly for a Government committed to net zero by 2050, almost a quarter (22%) stated that they would not be prepared to pay more in taxes or to change their behaviour: if this is an indication of the level of climate scepticism in the UK, this represents a significant share of the population. The proportion of people who preferred to pay more taxes (7%) was only slightly above that of people who stated they did not know (6%). Overall, however, over two thirds (71%) of respondents recognised that something would have to change, whether in the form of paying more taxes or changing their behaviour.

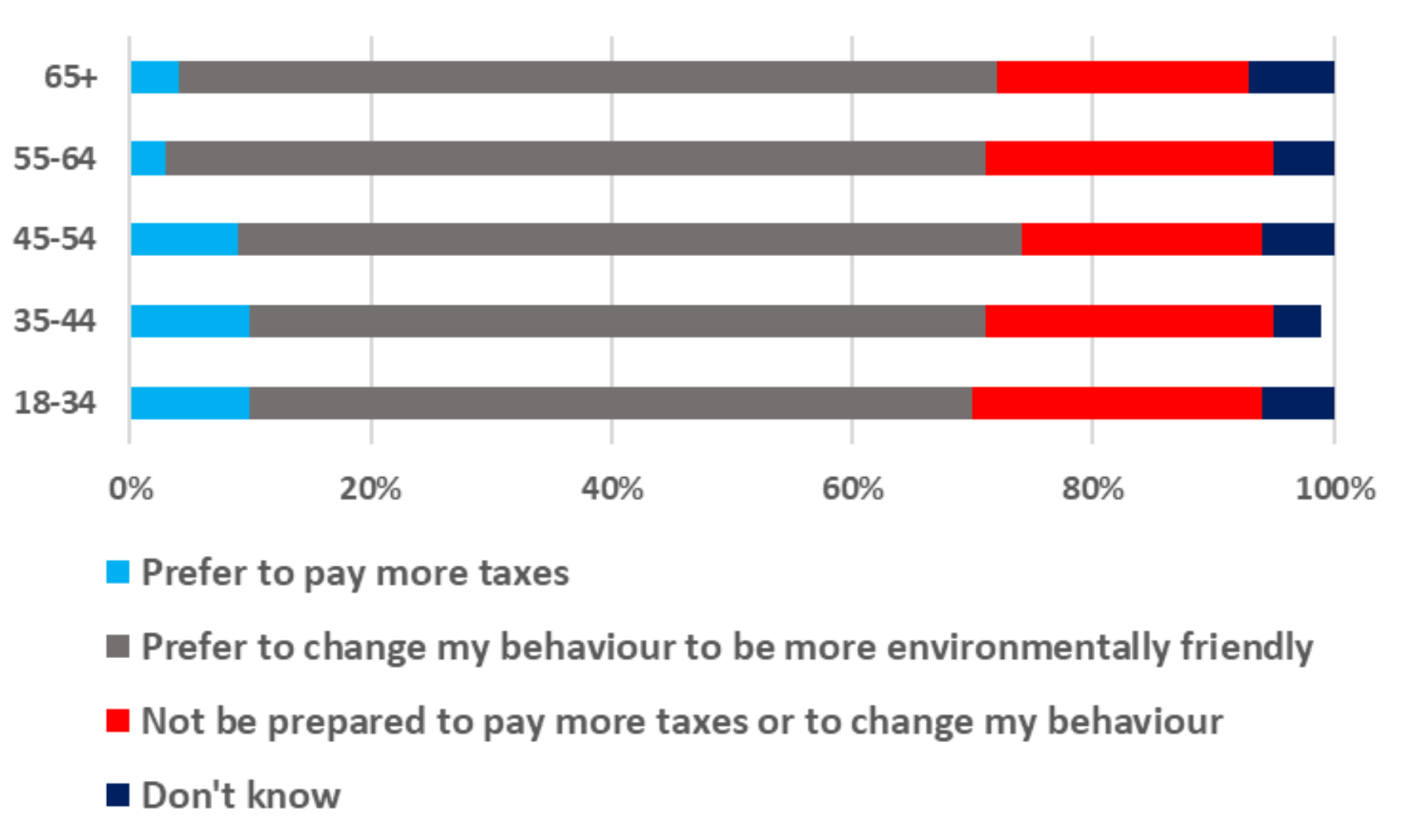

A closer examination of the data reveals a more nuanced understanding of which groups tend towards which climate-driven actions. Behavioural change, for instance, was more strongly supported by women (67%) than by men (62%), and by older age groups (68% of 55-64-year-olds and of over-65s) than by younger respondents (60% of 18-34-year-olds). The initially surprising age discrepancy, running contrary to popular belief that climate issues are primarily of interest to the young, may partly be explained by greater support for taxes among younger age groups (10% of respondents aged 18-34 and 35-44) than among older ones (3% of 55-64-year-olds). However, older respondents’ preparedness to change their behaviour is reinforced by other research which indicates older people in Britain are more likely than younger people to act in climate-friendly ways[5]. This is further supported by our survey data, which indicates that over-65s were, at 21%, less unwilling than those aged 18-34 and 35-44 (both 24%) to change their behaviour or pay greater taxes.

A closer examination of the data reveals a more nuanced understanding of which groups tend towards which climate-driven actions. Behavioural change, for instance, was more strongly supported by women (67%) than by men (62%), and by older age groups (68% of 55-64-year-olds and of over-65s) than by younger respondents (60% of 18-34-year-olds). The initially surprising age discrepancy, running contrary to popular belief that climate issues are primarily of interest to the young, may partly be explained by greater support for taxes among younger age groups (10% of respondents aged 18-34 and 35-44) than among older ones (3% of 55-64-year-olds). However, older respondents’ preparedness to change their behaviour is reinforced by other research which indicates older people in Britain are more likely than younger people to act in climate-friendly ways[5]. This is further supported by our survey data, which indicates that over-65s were, at 21%, less unwilling than those aged 18-34 and 35-44 (both 24%) to change their behaviour or pay greater taxes.

While middle- and high-earning respondents also preferred behavioural change (68% and 67% respectively), just 52% of low earners shared their sentiments. Respondents with higher qualifications were also significantly more likely than those with lower qualifications to support behavioural change to reduce emissions (73% compared to 57%)[6]. Climate scepticism also appeared higher in lower-income and groups with lower educational qualifications. Lower-earning respondents were, at 27%, more likely than their middle- and higher-earning counterparts (22% and 21% respectively) to state they would not change their behaviour or pay more in taxes, while those with lower qualifications were 10 points more likely than those with higher qualifications to express an unwillingness to change their behaviour and pay more taxes (26% vs 16%). This may reflect a well-documented class divide in climate engagement: polling by the Social Market Foundation, for instance, has found that lower-income voters were far less likely than their higher-income counterparts to support the transition to electric vehicles and more unwilling to pay for charging points[7]. Further research indicates that awareness of climate change is correlated (though not uniformly) with higher income and educational attainment[8]. A takeaway for the Government here may be to consider how - if it is to fulfil its net zero aspirations - it can support disadvantaged socioeconomic groups in switching to emissions-friendly habits and behaviours.

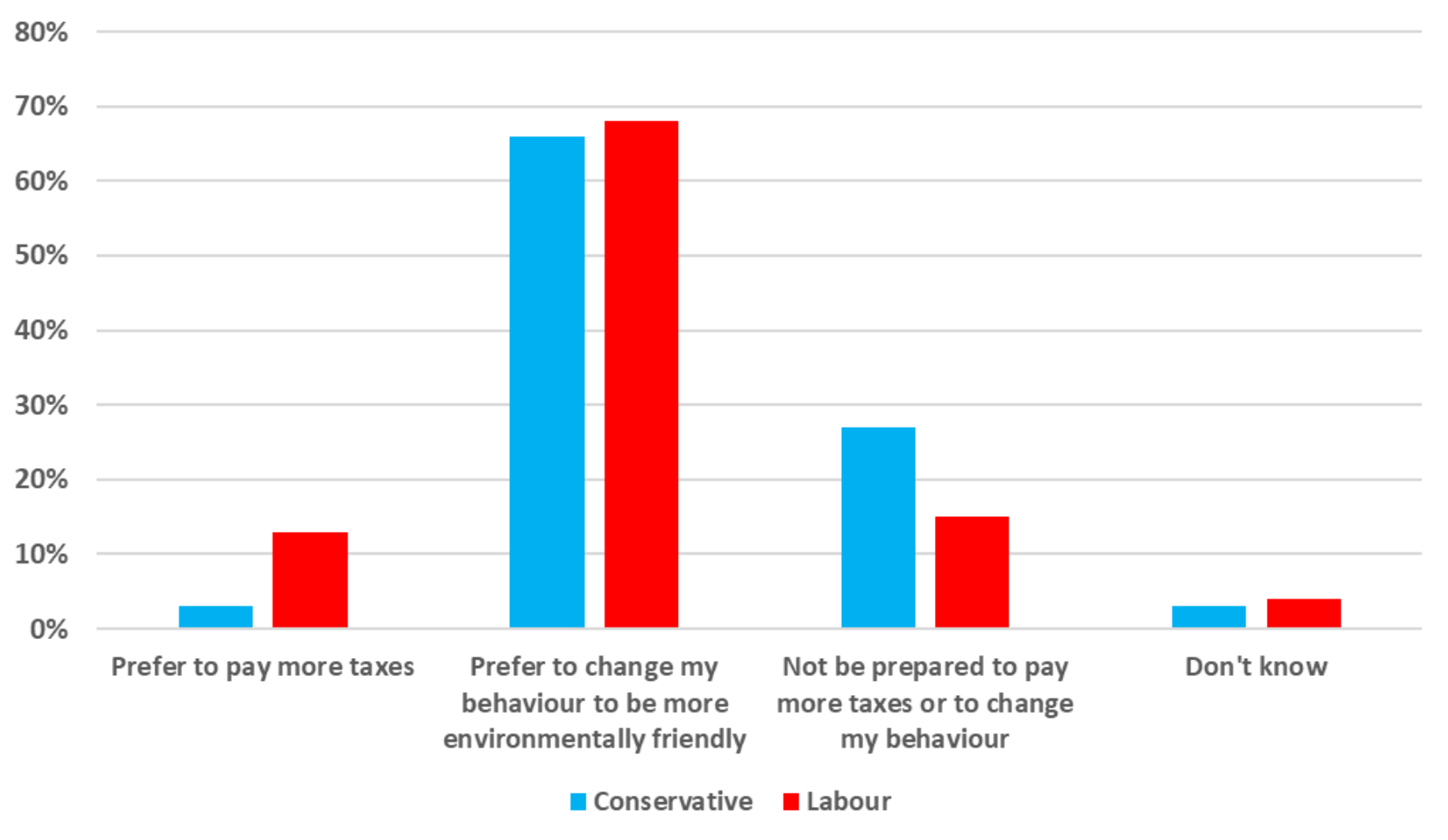

A breakdown of the results by political affiliation also unearths some interesting patterns. 69% of respondents who voted Conservative in the 2019 general election recognised that something in their lives, whether taxation or behaviour, would have to change to reduce their emissions: this figure was significantly lower than the proportions of other voters (81% of Labour voters, 81% of Liberal Democrat voters and 79% of ‘Other’ voters) who felt the same. With over one in four (27%) Conservative voters unwilling to make behavioural changes or pay more taxes, pursuing green policies may mean the current Government runs the risk of alienating a significant portion of its voter base: this risk could be why, in October, a Government blueprint for ‘successful behaviour change initiatives’ to discourage high-carbon activities, such as flying and eating meat, was withdrawn several hours after publication[9]. Furthermore, although Labour voters were, at 13%, twice as likely as the average respondent to favour higher taxes to reduce emissions, this option’s unpopularity among other voters and the general public speaks to the limitations of this proposal.

This survey signals a strongly held preference among Britons for behavioural change rather than taxation to reduce the UK’s emissions. While this may be unsurprising, given evidence that sustainable habits are increasingly widely practised by British consumers[10], it does indicate a way forward for the UK Government if emissions are to continue to fall. The low level of support for paying taxes hints at the unpopularity of punitive taxes or levies on consumption, such as those on fuel, meat or flying. This may reflect lower disposable incomes, given current high inflation and recent climate-unrelated tax hikes; on the other hand, perhaps support for climate action is broad but shallow, with people supportive in principle of green policies but not where this would impact them financially. Perhaps the Government will need to favour a ‘carrot’ rather than a ‘stick’ approach towards inducing citizens to adopt low-carbon behaviours, through green subsidies and financial incentives for electric vehicles, for instance, or for heat pumps and other forms of green heating. The polling certainly indicates that that would be citizens’ preferred option.

This survey signals a strongly held preference among Britons for behavioural change rather than taxation to reduce the UK’s emissions. While this may be unsurprising, given evidence that sustainable habits are increasingly widely practised by British consumers[10], it does indicate a way forward for the UK Government if emissions are to continue to fall. The low level of support for paying taxes hints at the unpopularity of punitive taxes or levies on consumption, such as those on fuel, meat or flying. This may reflect lower disposable incomes, given current high inflation and recent climate-unrelated tax hikes; on the other hand, perhaps support for climate action is broad but shallow, with people supportive in principle of green policies but not where this would impact them financially. Perhaps the Government will need to favour a ‘carrot’ rather than a ‘stick’ approach towards inducing citizens to adopt low-carbon behaviours, through green subsidies and financial incentives for electric vehicles, for instance, or for heat pumps and other forms of green heating. The polling certainly indicates that that would be citizens’ preferred option.

But changing one’s behaviour in principle is much different from changing it in practice, particularly if one is ignorant of the behavioural changes needed or of one’s own carbon-intensive activities. It may be the case that far more people are willing to state they will change their behaviour than will actually do so. If that is the case, the question becomes whether or not, in the absence of more punitive measures, people will change their habits extensively enough and fast enough for Britain to meet its net zero ambitions.

[3] ‘Planes, Homes and Automobiles: The Role of Behaviour Change in Delivering Net Zero’ – Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

[6] Based on the National Qualifications Framework: ‘What qualification levels mean’ – GOV.UK.

[7] ‘Electric vehicle switchover risks backlash without support for low-income voters’ – Social Market Foundation.

[10] ‘Four out of five UK consumers adopt more sustainable lifestyle choices during COVID-19 pandemic – Deloitte.

Polling was conducted by Survation via online polls. Data were weighted to the profile of all people in the United Kingdom, according to Office for National Statistics data. Polling was undertaken between 23-24 November 2021 and covered 1,005 people aged 18 and above living in the UK. Differential response rates from different demographic groups were taken into account.